Posted April 7, 2022

By JESSICA SEAMAN | jseaman@denverpost.com | The Denver Post

PUBLISHED: April 7, 2022 at 6:00 a.m. | UPDATED: April 7, 2022 at 6:05 a.m.

The students, mostly ninth-graders, had just finished lunch when they arrived for fifth-period, honors biology.

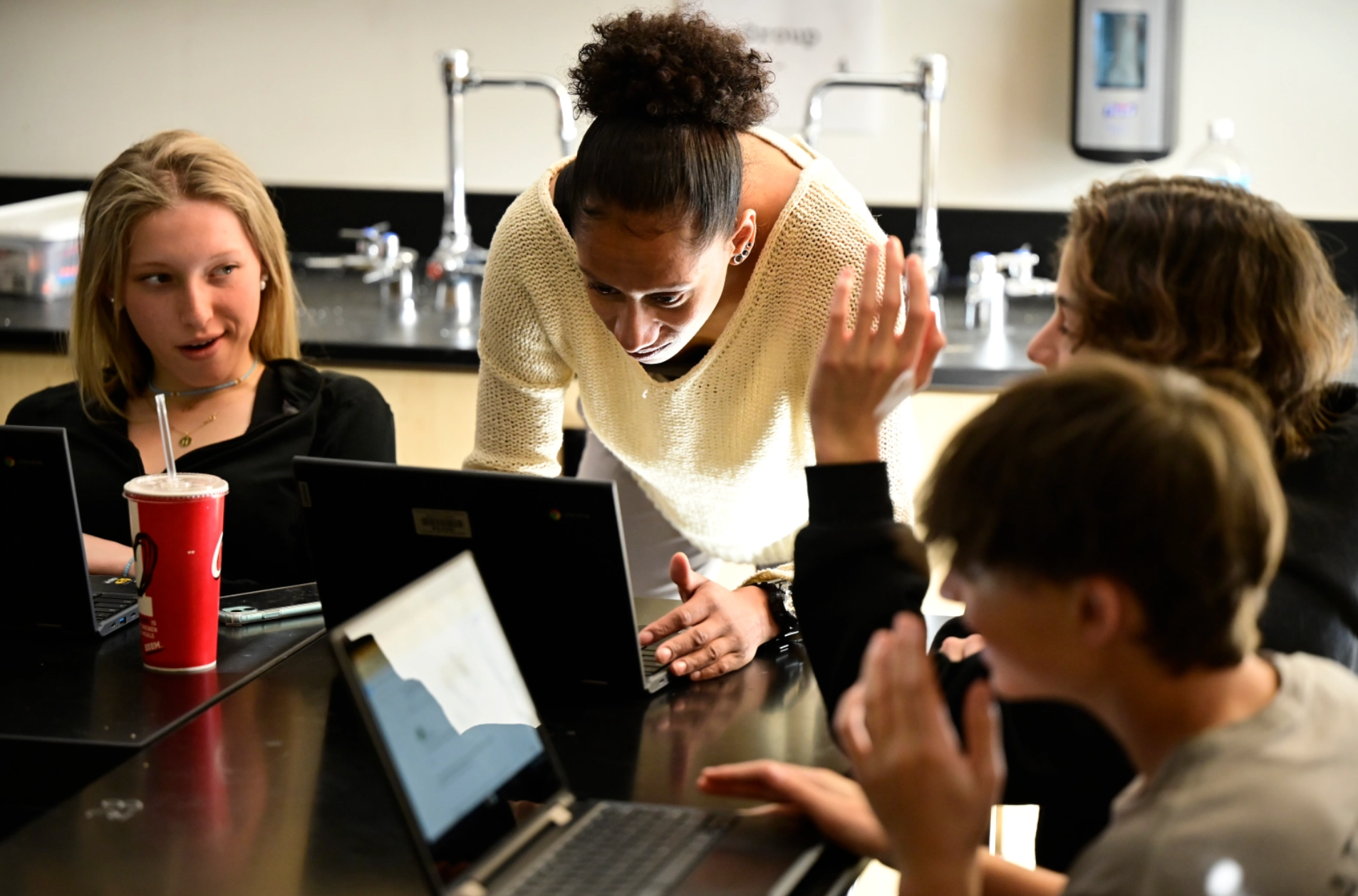

They sat at tables in groups of threes and fours and pulled out their laptops. One student rested his head on his desk. Their teacher, Neelah Ali, walked in as they settled and after grabbing their attention, she asked the students to open an assignment on their computer called “biome research.”

They were going to spend the class, Ali explained, answering questions about different places and their climates and wildlife. At the end of the assignment, there was an extra question, asking each student to create a model, such as a flow chart, to explain the relationship of the predators and prey that lived in the biome they researched.

“Almost all of you should get to that model,” the 32-year-old teacher said, adding that finishing the question was the only way to earn an “A” on the assignment.

But not everyone would make it that far in their work.

Instead, the question was included to help students adjust to having what Ali calls an “honors extension.” These are additional questions or projects that students will have to complete in order to earn honors credit when Denver’s South High School moves to its embedded honors program next year.

Schools across the nation, including those like South High in Denver Public Schools, are overhauling the traditional practice of having separate honors and regular courses — which they say leads to segregation — by putting all students in the same class.

In recent years, schools have sought to steer more students of color into advanced classes. Honors courses offer a higher level of study and are a stepping stone for students who want to take classes, such as advanced placement, or AP, courses, to earn college credit while in high school.

The tradition of separating students into honors and regular classes comes from the practice of tracking, which groups children together based on their academic performance, and it perpetuates racial and class inequality as students of color are placed in lower-level classes more often than their white peers, argued educators and an expert.

Tracking has a long history in U.S. education. It used to be based on social class as students who might work in factories were separated from their wealthier peers who were to become executives, said John Diamond, professor of sociology and education policy at Brown University.

And while the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 declared racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, tracking was used to concentrate Black and Latino children into lower-level classes in newly integrated schools. The tracking system has evolved as children went from being grouped together in all of their classes based on academic performance to the current method where students take honors or regular classes depending on their skill in a specific subject, Diamond said.

“There’s a growing sense that we can create classrooms where more kids have access to higher-level content and deal with the disparities that tracking creates,” he said, adding that tracking is “second-generation segregation.”

However, the changes to high school honors programs are facing resistance from parents, such as Mari Paz, a mother of a South High ninth-grader, who wants to know, “How is this better for my kid?”

“We chose South because of the curriculum that they have and now they are changing that,” Paz said.

The school made the changes without any input from the parents, she said, which created confusion after the principal sent an email to families in January notifying them of the move to the embedded honors program next year.

Among the confusion, Paz said, is how teachers will keep classes at a rigorous pace when students are on different levels and how exactly will the changes dismantle racism. She pointed out that she’s an immigrant and her son is in three honors classes.

“I don’t think this has anything to do with minorities because he is a minority,” she said.

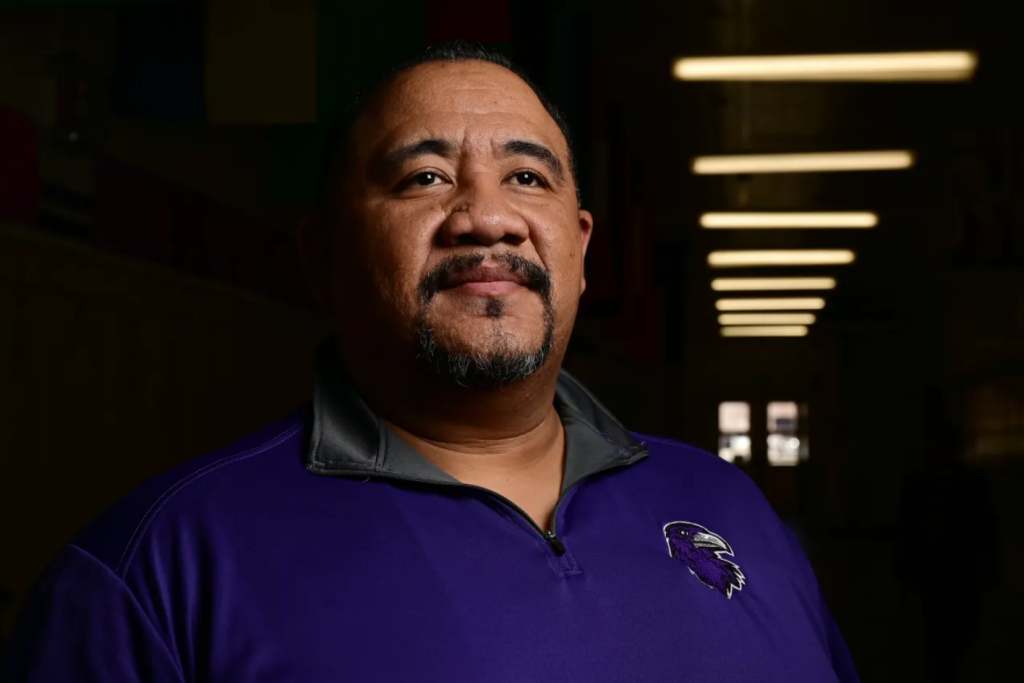

When Bobby Thomas became principal of South High four years ago, the 44-year-old found that the storied institution did not fully reflect its diverse student population and reputation as a safe haven for refugees and immigrants.

Students come to the school, a red brick building guarded by gargoyles in the city’s affluent Washington Park neighborhood, from more than 50 countries. Malala Yousafzai, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Pakistani activist for girls education, even visited in 2016 after hearing about the school.

But the school, which took on its current name in 1926, is one of the city’s four directional schools and drew inspiration from the Civil War when naming the school’s former mascot, the Rebels, Thomas said. The mascot was changed to the Ravens in 2020.

Other symbols of the American South’s racist history have also decorated the school for decades. South High’s student newspaper used to be named “The Confederate” and a Confederate battle flag covered the school’s yearbook.

It wasn’t just the mascot or yearbook that didn’t reflect the school’s diversity. Thomas could walk the school’s halls and peek into a classroom and immediately know whether it was an honors class or a regular one simply by the racial demographics of the students in the room.

And as a leader of color, he said, that was hard to face.

“That is not what we stand for here at South,” Thomas said.

So, to change that, teachers began experimenting with ways to make honors classes more available to all students.

The idea is that students who traditionally choose to take honors courses are more likely to have support outside of school via parents and tutors who are helping them prepare for college and are pushing them toward more advanced classes.

But that support, which costs money, isn’t there for every student and the gap between students has only grown during the pandemic as learning was disrupted across the U.S.

By putting all students in honors classes when they start high school, South High and other schools are giving teenagers who might not have previously considered such courses the opportunity to learn at a higher level, educators said.

Annie Espino, a junior at South High, is one student who has experienced this first-hand. The 17-year-old was intimidated by honors and advanced placement courses and that fear initially kept her from seeking out those classes.

But now, Espino is taking four honors classes this semester because of the honors-for-all pilot programs at South High. She didn’t even know that her class studying Hispanic literature was an honors course until after she enrolled.

“I’m Hispanic,” Espino said about why she took the course. “I wanted to hear more about my literature.”

The challenge South High and other schools are facing is figuring out how honors-for-all should work, including how to give honors credit when students in the classroom are learning at different levels.

“We’re trying to navigate this equity concern about weighted GPA,” Ali, the teacher, said. “We have to prepare students for college and we wish we could get rid of it, but we can’t. We still have to give GPAs. We still have to give grades.”

South High first tried coding all of its English classes as honors courses, but the unintended consequence was that every student received honors credit even if they didn’t demonstrate higher levels of proficiency, Thomas said. The science and math departments have piloted different versions of the program that are based on the depth of students’ work in class.

And starting next year, South High will make its embedded honors program unified across its four core subjects: English, math, science and social studies. None of these classes, which are mostly for ninth-and tenth-graders, will have honors designations, but every student will have the opportunity to earn honors credit if they receive at least a “C” in class at the end of the semester and show proficiency on the end-of-course assessments.

“This is another way where if you identify as a student of color or if you identify as white, you’re going to be in class with the same opportunities when it comes to all of our (core classes),” Thomas said.

Making all students take honors classes is just one way schools are trying to make their classrooms fairer. California, reported The New York Times, has looked at overhauling math instruction by proposing guidelines that would recommend against moving certain middle-school students into advanced classes and having schools offer alternatives to calculus.

And in Virginia, a magnet school eliminated its standardized testing requirement. Although, a judge earlier this year ruled that the change, which was made to bring in more Black and Latino students, left Asian American students “disproportionately deprived of a level playing field,” reported The New York Times.

Other Denver schools have launched similar initiatives as South High, including East High School and George Washington High School. However, the district does not have data on how many schools provide honors for all, said spokesman Will Jones in an email.

The changes to high school honors programs are drawing backlash from parents and students who fear honors credit is being eliminated entirely or question how teachers will be able to accelerate learning when students are at different levels.

“Cramming students of different abilities into the same classes has forced teachers to simplify their instruction and make curriculums less rigorous,” wrote Kalina Kulig, a senior at George Washington High, in a recent opinion column for The Denver Post.

It’s unsurprising that parents of children who have traditionally had access to honors classes are resisting the changes; they know they are receiving an advantage that can help students who want to college, said Diamond, the professor at Brown University.

“It’s a separation and it’s sort of a distinction people want to have so when their kid graduates they can get to an Ivy League school,” Diamond said, calling the efforts “opportunity hoarding.”

Another parent, Michael McMurray, said he saw the benefits of combining students of different levels in the classroom when his son Luca was at Morey Middle School, which houses one of the district’s magnet programs for highly-gifted students.

But he’s also experienced with his own children how challenging it is to meet their individual educational needs. Luca is a ninth-grader at George Washington High. The 12-year-old, who accelerated two grades, finds the pace of his honors English class too slow. The class that challenges him the most is one normally taken by 11th and 12th graders: international baccalaureate, or IB, calculus.

“It’s really, really hard to come up with a one-size-fits-all curriculum and meeting kids where they are is really important and also really challenging,” McMurray said.

Thomas, the principal at South High, is more worried about students who perform at a lower level because he says the pacing of the classes will be rigorous with deeper conversations about what is being taught and teachers won’t have time to address every students’ needs.

He is hiring one more interventionist and a social worker to provide students with more support next year. The school’s teachers are also focusing on how to support students at different learning levels and what that differentiation looks like in their professional development this spring.

“Part of it is identifying what it takes to earn honors so all students know what they need to achieve it,” Thomas said. “It’s going to be tough on our teachers. It’s going to be tough on our students because there’s differentiated levels.”

During the middle of her biology class, Ali went to the whiteboard and began showing her students what she is looking for when they complete their honors extension model. She drew a chart showing that bears eat fish and fish eat insects and insects eat dead, decaying things.

“You want to make sure you have dead stuff on there,” she told the class. “Why?”

“Things die,” one student answered.

“It’s easy food,” another said.

Freshman Sadie Sutton was one of the students to complete the honors model during the class.

“It’s pretty easy,” she said, adding that it’s incorporated in students’ assignments and she can finish her work quickly.

Ali wants all of her students to do the honors work, but she knows that not everyone likes school or science. She tries to engage them in the deeper work by drawing on their interests and has found that by the end of the year almost every student will have tried at least one honors assignment.

Ali weaved through students’ desks asking them about their biome and wildlife. The class was almost over when she approached student Jameson Collins and encouraged him to complete the predator and prey model.

“It’s more than honors credit, right?” Ali said. “It’s also an extension of your learning.”

The ninth-grader doesn’t normally do the honors work, but maybe this assignment will be different.

Collins, when asked later if he would do the model, responded: “Most likely.”